I want to participate in the ______ minyan.

Parshat Vayera 5780

In this week’s parshah, we read of the birth of Isaac to Abraham and Sarah in their old age. The Torah tells us that the reason Sarah named her son by the name Isaac was due to the explanation that “God has made happiness for me” (Genesis 21:6). The Alshekh explains that since the name ‘Yitzchak’ could have been explained as referring to Sarah’s inward laughter when the angels predicted this birth, the Torah therefore makes a point of explaining that Sarah saw a different significance in that name. Abraham made a great feast when Isaac was weaned, to show that Sarah had become youthful; able to nurse Isaac all these long months. Isaac was taken off the mother’s breast because he was old enough, not because Sarah could not nurse him anymore.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe used this parshah as a forum to discuss the significance of Bar/Bat Mitzvoth in today’s world. It is explained to us that Isaac was weaned when he was 13 years old; the age a boy is to become responsible for his own deeds and becomes a man. Therefore, the Rebbe, in a discourse given over 30 years ago, told the following story which is still very much relevant today: ‘He was still years away from his Bar Mitzvah, but his parents were far-sighted. They found a synagogue, which wouldn’t make heavy demands of the boy, and certainly would expect little yiddishkeit of the parents. The lad would understand that a Bar Mitzvah is a graduation of sorts – when he would graduate from Judaism. He was urged, no, lavishly bribed, to study his haftora, possibly by transliteration. The youngster is made to understand that his father had a Bar Mitzvah himself, and he joined the synagogue; he pays dues, even attends on occasion, and all for the sake of the Bar Mitzvah. The neighbor’s son had a Bar Mitzvah, so how will it look if “our son” doesn’t have one too? And father’s business associates also expect him to have one. After all, everyone has a Bar Mitzvah. The boy is not stupid, nor are his feelings dull. He can understand and he can feel what the purpose of it all really is. Father and Mother are completely occupied with business and party planning, and the son is left to his own reasoning. Can he possibly be serious about the significance of Bar Mitzvah? He saw none of its true meaning in his father or mother; neither in their own personal conduct, nor in the upbringing they gave him. He was taught that he must do what ‘everybody’ does, or else his parents will be put to shame. Naturally, his reaction is to close the door, to go and seek elsewhere something more meaningful to him, to seek without guidance, without directions. He knows that his parents have nothing authentic to give him, for they never truly educated him ‘Jewishly’, and the smattering of Jewish teaching they gave him was only to outdo the neighbors – not with sincerity, and not because it meant anything to them. The boy reflects on the Bar Mitzvah itself. He had it on Shabbat. Why on Shabbat? Because, he is informed, that is a holy day. What makes it holy, the youth wonders. His father and mother conduct business on the Sabbath, and they do exactly what they would do on any other day. He still doesn’t understand how Shabbat is holy. He is given the answer that the congregation has engaged a rabbi who is a holy man and he ‘carries’ the holiness of the congregation on his shoulders. He will be the one to keep all the important laws.

Is it a wonder that such an upbringing creates a chasm between parents and children? When the parents tearfully plead one day with their children, “why have you humiliated us?’ they will retort bitterly, “Did you ever give me something more meaningful to stand on? You taught me to imitate others and to seek their approval. That’s all I ever learned from you!”

A Jew is to imitate no one, except God. As it is written in Tractate Shabbat 133:b: “As He (God) is merciful, so shall you be. As He is kind, so shall you be.” This is not imitation; He is not separate from God and in acting as God does, he is acting naturally. The boy or girl will then know what they are, and what they lack, and where to find a firm foundation upon which to stand all their lives.

The parshah concludes with the listing of the descendants of Nachor (Genesis 22:24). It states in verse 22 that “Bethuel fathered Rebecca.” This is the principal line of the whole paragraph. Rabbi Chayim Ben Attar asks why the Torah had to bother to list all the other descendants of Nachor including those from his concubines. He answers that the Torah is reminding us that ever since the spiritual poison of the original serpent permeated Adam, purity could no longer exist in isolation. The birth of even the most perfect human being is invariably accompanied by the birth of impure people who lie in wait for the pure. By telling us of the other descendants of Nachor, the Torah indirectly extols the virtue of Rebecca, mother of all that is holy, whom, despite the environment she grew up in, shone forth with her many virtues.

Prepared by Devorah Abenhaim

Cantorial

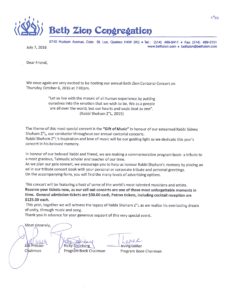

Click on the picture to enlarge it

Parshat Devarim on Moshe and Yehoshua

Today I will begin to put the dread of you and the fear of you upon the nations that are under the whole Heaven …” (Devarim 2:25)

“It was taught: Just as the sun stopped for Yehoshua, so too did it stop for Moshe … How do we know about this for Moshe? From the comparison of the words “I will begin” [in Yehoshua 3:7] and “I will begin” [in our parshah] … ” (Avodah Zara 25a)

Many people are familiar with the miracle of the sun standing still for Yehoshua in his famous battle against the kings of Canaan who had attacked Givon (Yehoshua 10:1-20). Far fewer are aware that the same miracle had happened previously for Moshe in his battle against Sichon (Bamidbar 21:21). Even the Torah didn’t publicize Moshe’s miracle forcing the Talmud to look for an allusion for such a spectacular event! Why? The answer comes from understanding the nature of a plant. Rabbi Pesach Winston explains: Just as Moshe and Yehoshua can be compared to the sun and the moon, so too can they be compared to the revealed part of a flower, and the roots that lie below the ground. Though the revealed part of the flower seems to be the essence of the plant, in truth, it is just the revealed expression of all that is rooted in the ground, hidden from the eye. However, all that grows above ground must have some root in that which grows below ground. Moshe had been more than just a great leader; he was the “root” of all that Yisroel was and would ever be. All the greatness the Jewish people would ever flower into would be rooted in Moshe, in accomplishments he himself achieved. This is why he was asked to climb the mountain and look at Eretz Yisroel; according to the Pri Tzaddik, this was G-d’s way of having Moshe spiritually imbue the land with his potential and greatness, to benefit the Jewish people long after his death.

Hence, the Talmud’s question becomes: If we see that Yehoshua was able to cause the sun to remain in the sky longer than normal, where was this rooted in Moshe’s lifetime? For this the Talmud reveals a “hidden” source and root, and underlying message: Though Moshe has physically left the world, his spiritual greatness continues to act as the root for all the “flowers” that have blossomed, and continue to blossom, throughout Jewish history.

Prepared by: Devorah Abenhaim

Parshat Emor On the Kohen’s duty to his parents

In last week’s parsha we saw the mitzvah of “Honor your father and your mother.” So important is this mitzvah that it appeared on the side of the Tablets that dealt with mitzvos between man-and-G-d (the first four mitzvos concern the relationship between man-and-G-d, whereas the last five of the Ten Commandments, beginning with murder, are of the relationship between man-and-man).

If so, then it comes as a surprise to read in this week’s parsha the following: “The Kohen Gadol (High Priest) of his fellow kohanim, upon whose head the oil of anointment was poured and who was consecrated to wear the [holy] clothing, [the hair] of his head should not be in disorder, nor shall he tear his garments. Neither shall he go in to any dead body, nor defile himself for his father or his mother; nor shall he leave the Temple or profane the Temple of G-d … “(VaYikrah 21:10)

Now it is true that, technically, the mitzvah of honoring one’s father and mother ends with the parent’s death, and it is a mitzvah of honoring the dead that replaces it. Still, the line between the two is somewhat gray, and, at the very least, there is the appearance of a lack of respect for one’s parent should a child’s final respects not be paid properly.

When two mitzvos “collide” like this (being the Kohen Gadol and properly honoring one’s deceased parent), it is an indication that a more sophisticated understanding of each mitzvah is necessary.

Rabbi Pinchas Winston explains:The essence of the mitzvah of honoring one’s father and mother is the concept of “hakores hatov” (appreciating the good). Parents give life to a child, and whether or not they properly sustain that life, still, the gift of life is still the gift of life. In appreciation of that gift, a child is supposed to maximize the opportunity of life, which is the greatest honor the child can accord the parent. This too is going to become the basis of one’s relationship to G-d once the child matures into an adult.

One of the most important roles the Kohen Gadol played was to be a constant reminder of the source of good in life, and to enhance the appreciation of the entire Jewish nation of the gift of life, and the gift of Torah and mitzvos. He did this in many ways, but primarily, it was his singular devotion to G-d and spiritual perfection to the “nth degree” that best transmitted this message to the Jewish people in the Temple and beyond.

Hence, though normally one’s respect for his parent achieves the same goal, in the case of the Kohen Gadol, to leave his place of holiness and to break with his service of G-d would have accomplished just the opposite, since as the Kohen Gadol, he already symbolized the goal of showing such respect.

Prepared by Devorah Abenhaim